Created in 2000, SWGfL (together with partners Internet Watch Foundation | IWF and  Childnet) form the UK Safer Internet Centre - Part of the European Insafe network of national centres. For over twenty years its specialists have worked with Governments, schools, public bodies, International Agencies and industry on appropriate policy and actions to take regarding safeguarding and advancing positive online safety.

Childnet) form the UK Safer Internet Centre - Part of the European Insafe network of national centres. For over twenty years its specialists have worked with Governments, schools, public bodies, International Agencies and industry on appropriate policy and actions to take regarding safeguarding and advancing positive online safety.

SWGfL has been at the forefront of online safety for over two decades; directly and indirectly supporting victims of online harms through its Helplines

Professionals Online Safety Helpline

Advising those working with children about safeguarding online since 2011

Revenge Porn Helpline

Supporting adults who are victims of non-consensual intimate image abuse since 2015

Report Harmful Content

Supporting and representing victims to report and remove of legal but harmful online content since 2019

SWGfL has developed several innovative and award-winning digital solutions to ensure everyone can benefit from technology free from harm and these include:

Stop Non-Consensual Intimate Image Abuse - StopNCII.org

Worlds first device side hashing technology supporting (adult) victims of non-consensual intimate image abuse to prevent their content being shared on social media anywhere in the world.

Online Safety Self-Review Tool for Schools | 360safe

Self-Assessment solution supporting over 16,500 UK schools in reviewing their online safety policy and practice.

ProjectEVOLVE - Education for a Connected World Resources

Launched in 2020, a complete children’s digital media skills framework with activities and assessments used by over 43,000 UK teachers

Given this wealth of experience and understanding, to further its charitable purpose, SWGfL publishes a series of annual reports sharing its knowledge, experience and information, most notably

ReportHarmfulContent Annual Report 2021 | SWGfL

2021data and insights from SWGfL’s Report Harmful Content platform supporting those experiencing legal but harmful online content

Revenge Porn Helpline Cases and Trends of 2021 | Revenge Porn Helpline

2021 research and information regarding SWGfL’s Revenge Porn Helpline - 0345 6000 459 that was created in 2015 and is the world's first helpline supporting adults who are victims of non-consensual intimate image abuse

England Schools: Online Safety Policy and Practice Report 2022 | SWGfL

First published in 2009, this annual assessment report highlights school's policy and practice providing insights from the 16,500 schools across the UK using Online Safety Self-Review Tool for Schools | 360safe

ProjectEVOLVE Evaluation Report | SWGfL

First report highlighting the strengths and gaps of children’s digital media literacy skills across the UK

Online Safety Bill Written Evidence

The following extract is from its written submission to the Online Safety Bill in Summer 2022.

Main points

- Part 3 Chapter 2 - Impartial dispute resolution - The Online Safety Bill actually removes existing user redress by dismantling existing obligations on services to operate dispute resolution mechanisms.

- Part 10 – Intimate Image Abuse – include conclusions from the upcoming report from the Law Commission on the taking, making and sharing of intimate images.

- Part 3 Chapter 7 – Defining Legal but Harmful - Retaining a focus on victims and the impact of legal but harmful content, Parliament should only approve the types of ‘legal but harmful’ content that platforms must tackle if all those identified here are included

- Part 3 and Part 7 Chapter 2 - Services within Scope and Categorisation – With limited duties related to legal but harmful content beyond category 1, it is unclear which providers and services will fall within this category and ultimately little to inhibit the spread of legal but harmful content

- Part 8 Chapter 2 - Super-Complaints - Details have to be published regarding the criteria that an entity must meet in order to make a complaint to Ofcom

The latest Online Safety Bill drafting actually removes existing victim support by dismantling existing obligations on services to operate dispute resolution mechanisms

Part 3 — Providers of regulated user-to-user services and regulated search services: duties of care, Chapter 2 — Providers of user-to-user services: duties of care

It is important to draw Parliament’s attention to the current Video-sharing platform (VSP) regulation - Ofcom that requires ‘Video Sharing Platforms’ (1) to ‘provide an impartial dispute resolution procedure’. The regulation details this impartial appeals process requirement. With its current lack of any independent ombudsman provision, and as the Online Safety Bill will supersede the existing Video Sharing Platform Regulations, this will have the effect of dismantling and removing the current recourse that victims of legal but harmful content currently have.

SWGfL very much supported the conclusions of the Joint Committee on the Draft Online Safety Bill (2) “that service providers’ user complaints processes are often obscure, undemocratic, and without external safeguards to ensure that users are treated fairly and consistently.” In addition, that “it is only through the introduction of an external redress mechanism that service providers can truly be held to account for their decisions as they impact individuals.”

1 Notified video-sharing platforms - Ofcom

2 Draft Online Safety Bill (parliament.uk) para 454-457

It is particularly disappointing that the reports recommendation that “The role of the Online Safety Ombudsman should be created to consider complaints about actions by higher risk service providers where either moderation or failure to address risks leads to significant, demonstrable harm (including to freedom of expression) and recourse to other routes of redress have not resulted in a resolution” was disregarded.

Dismissing the opportunity for victims to seek independent recourse or appeal demonstrates a lack of compassion for the distressing impact that legal but harmful content has on victims. User redress and victim support have to be an intrinsic part of the wider ecosystem, requiring platforms to have user redress and victim support measures, policies and systems in place. This user redress and victim support has to be transparent as without it, understanding if platforms are adequately supporting their users will be invisible.

[Online Safety Bill, Part 3 — Providers of regulated user-to-user services and regulated search services: duties of care, Chapter 2 — Providers of user-to-user services: duties of care.] Section 18 has to include a duty to operate 'Impartial Dispute Resolution Service'. Where complaints are made and services fail to action or resolve the complaint, users should have access to impartial dispute resolution recourse to independently resolve their complaint.

Section 18 of Part 3, Chapter 2 of the Online Safety Bill should include

A requirement for all providers to implement a dispute resolution procedure, regardless of the size or nature of the platform. This is a separate requirement to the requirement to take and implement appropriate measures to protect users from harmful material. Dispute resolution procedures must be impartial and must allow users to challenge a services implementation of a measure, or a decision to take, or not to take, a measure. A person who provides a video-sharing platform service must provide for an impartial out-of-court procedure for the resolution of any dispute between a person using the service and the provider relating to the implementation of any measure set out the services complaints process or a decision to take, or not to take, any such measure, but the provision of or use of this procedure must not affect the ability of a person using the service to bring a claim in civil proceedings

This drafting is extracted from existing Ofcom VSP regulations that currently require platforms to operate such an impartial dispute resolution service. By not including this will remove existing safeguards. With the object to make the UK the safest place to be online, it is unfeasible that this is not achievable without impartial or independent arbitration of complaints to stand for users and victims

Further note related to the term ‘Easily Accessible’ in context of

(3) A duty to include in the terms of service provisions which are easily accessible (including to children) specifying the policies and processes that govern the handling and resolution of complaints of a relevant kind.

In line with the age appropriate design code, services should be required to publish their policies and processes, specifically terms and conditions and privacy statements in a manner according to the minimum age that the service is accessible by. For example if the service is accessible for users over age 13, the policies should be published in a manner that a 13 year old can be reasonably expected to understand using, for example reading indexes Gunning Fog Index (gunning-fog-index.com)

Intimate Image Abuse

Part 10 — Communications offences

We would ask that Parliamentarians remain mindful of the upcoming report from the Law Commission on the taking, making and sharing of intimate images. The Government commissioned the review in recognition of the reality that the Criminal Justice and Courts Act, section 33 was failing victims in an evolving landscape of online abuse and violence against women and girls. The OSB coming at the same time that this comprehensive report is due represents a significant opportunity for the UK to remain at the forefront of global efforts legislatively to combat this growing harm.

We have contributed extensively to the work of the Law Commission and are hopeful that the following recommendations will be incorporated into their report:

- The removal of the ‘intention to cause distress’ requirement which is a barrier to prosecution for victims and extremely difficult to prove for police and prosecutors;

- The sharing of intimate images without consent should be classified as a sexual offence. This would guarantee victims the right to anonymity. The lack of anonymity is a known barrier to victims reporting this offence or supporting prosecutions going forward. Someone who has had their most private moments exposed without their consent should be protected from further violation by being identified through court processes.

- The inclusion of intimate content produced via deepfake or nudification technologies: we know that such content causes equivalent harm to other forms of intimate image abuse and with improvements in technological capabilities and their availability, it is a behaviour becoming more and more widespread. The drafting of such legislation should be future-proofed to take into account new developments that may be used to abuse and cause harm.

- The definition of a private sexual image should be broadened: the definition is currently very strict and fails to take account of the context around an image that may make it more intimate. For example, on the face of it, a bikini shot from the beach is very similar to an underwear shot in a bedroom, but the context of that image makes one much, much more harmful if shared than the other.

It is important to acknowledge that intimate image abuse is a gendered harm. In the seven year history of the Revenge Porn Helpline, 66% of those seeking support have been female, with 18% male and 15% not known.

The impact on women is disproportionate as we see repeated extreme distress, depression, suicidal ideation, impacts on jobs and careers, damage to personal and family relationships and withdrawal from online spaces and engagement.

We are pleased to see that the OSB includes a new offence to cover “Sending etc photograph or film of genitals” (Section 156). However, we note that the new offence as drafted includes the intention to cause distress or for the purpose of sexual gratification. We would urge lawmakers to avoid making the same error as was made in the CJCA s 33 which also includes the intention to cause distress. The motivations behind behaviours of intimate image abuse are varied and we would prefer to see the focus on the lack of consent of the victim than potential motivations of perpetrators.

Defining ‘legal but harmful’ content

Part 3 — Providers of regulated user-to-user services and regulated search services: duties of care Chapter 7 — Interpretation of Part 3 Section 53 and 54

SWGfL has supported victims of legal but harmful content for the last two decades. Whilst the term ‘harmful content’ can be very subjective, legal but harmful content can be just as catastrophic as illegal content.

Whilst Report Harmful Content was finally launched in 2019, it took more than five years to prepare, with the majority of this time spent developing its definitions and understanding of legal but harmful content.

Report Harmful Content exists to support and represent victims of legal but harmful online content to report. With a detailed understanding of platform terms and conditions, it represents victims in reporting and removing legal but harmful content. When it reports content, its takedown rate is 89%.

Report Harmful Contents definitions of legal but harmful is the foundation of the platform. Developed over a five-year period, these definitions are based on a variety of considerations, most notably victim experiences and platform terms and conditions (or community standards). Legal but Harmful content extends to

- Abuse - A broad term that covers forms of abuse committed on a social network, website, gaming platform or app. It is verbal but also include image based abuse.

- Bullying and harassment - Hurtful language that targets an individual or group of people, trolling, spreading rumours and excluding people from online communities. In the case of harassment, the behaviour is repeated and intended to cause distress.

- Threats - 1. Hypothetical. Expressing disagreement by making non-serious threats that are highly unlikely to be carried out. These would not normally go against community standards on social networking sites unless there are other factors to be considered. 2. Credible. Threats that poses real life danger, putting someone at immediate risk of harm e.g. a threat to life. Other threats of this kind could be “outing” someone’s behaviour to blackmail them. They may be used to coerce someone into doing something they don’t want to e.g. sending an intimate image or another behaviour they may later regret.

- Impersonation - The assumption of another person’s identity to harass or defraud, including creating fake accounts, or hijacking accounts usually with the intent of targeting an individual.

- Unwanted sexual advances - Gender-based abuse and can take the form of highly sexualised language or persistent and unsolicited messages, often of a sexual nature. The sender will have complete disregard for whether or not the person on the receiving end wants to receive these advances.

- Violent content - Graphic content including gore content, such as beheading videos or scenes which glorify animal abuse. Most of which will be against various platforms community standards.

- Self-harm/suicide content - Most platforms do not allow any content that encourages, instructs or glorifies self-harm or suicide. Some platforms have processes in place for safeguarding users who view or share this type of content.

- Pornographic Content - Adult (nude or sexual) content which is not illegal but breaches the terms of most online platforms.

There are some further specific types of Legal but Harmful content that were identified and included here (reportharmfulcontent.com), including:

- Sextortion

- Catfishing

- Hate Crime

- Fraud

- Spam

- Unsolicited Contact of an Adult Nature

- Incapacitation

- Underage Accounts

- Privacy Rights

- Intimate Image Abuse

Published in its first Report Harmful Content Annual Report 2021 | SWGfL, the Annex A details the report conclusions

Impact of Legal but Harmful content

Recognising that defining legal but harmful content should release pressure or incentive for platforms to over-remove legal content or controversial comments, however it dramatically increases the importance of adequately specifying the scope and detail of this definition.

The impact of legal but harmful content can be catastrophic on victims

To evidence this, in 2020, during Report Harmful Contents first full year of operation, 4% of those seeking its support expressed suicidal ideation (3) meaning the platform has potentially helped to save 25 lives. For example, one victim who was being repeatedly harassed by a relative over social media, tried to report her issue to the police, with no success. At the point she made a report to ReportHarmfulContent she was desperate. She said: ‘I have (already) tried to commit suicide with an overdose but she is still carrying on I don’t know what to do anymore other than another overdose’.

Aside from suicidal ideation, other reported mental health impacts included:

- Distress (70%)

- Anxiety (52%),

- Decline in social functioning (36%),

- Depression (27%),

- Agoraphobia (5%)

- Post-traumatic stress disorder (4%).

(3) Report Harmful Content Annual Report 2021 (swgfl.org.uk)

18% of those seeking support experience negative mental health impacts having had sought medical treatment (e.g. medication or therapy).

In addition to causing new mental health problems, harmful online content was described as exacerbating existing mental health issues. For example, one caller had recently left an abusive relationship. Her ex-partner created numerous fake social media profiles in her name, with the aim of continuing his harassment of her. She said ‘I had PTSD because of him and this had settled with a lot of therapy, but has recurred since all this online abuse started again’.

Laying further evidence, the Revenge Porn Helpline routinely supports victims who express suicidal thoughts. To exemplify this, Leigh Nicol, Scottish footballer, speaks on victim impacts of intimate image abuse - YouTube and the impact her situation had on her life

There are individuals who have amplified vulnerabilities to legal but harmful content. SWGfL has worked closely with the Thomas family, whose daughter Frankie tragically took her own life in September 2018 after viewing suicidal content and that the Coroner rules school failed teen who took own life - BBC News. Frankie was 15 and attended an Independent Special School as she had autism. Much research highlights that Special Educational Needs (SEN) extends the online risks, for example Internet-Matters-Report-Vulnerable-Children-in-a-Digital-World.pdf (internetmatters.org) identified that, ‘of these children and young people with special educational needs were 27% view sites promoting self- harm compared to 17% of young people with no difficulties’.

Retaining a focus on victims and the impact of legal but harmful content, Parliament should only approve the types of ‘legal but harmful’ content that platforms must tackle if all those identified here are included

There is much experience of both definition and reporting of ‘legal but harmful’ online content, specifically the UK Safer Internet Centre. How is the Online Safety Bill ensuring that the proposed definitions of legal but harmful content reflects this experience?

Services within Scope and Categorisation

Part 3 — Providers of regulated user-to-user services and regulated search services: duties of care

Part 7 — OFCOM's powers and duties in relation to regulated services

Chapter 2 — Register of categories of regulated user-to-user services and regulated search service

Clause 81 - Register of categories of certain Part 3 services

It’s particularly important to draw the committee’s attention to the duties, categorisation and register of providers of regulated user-to-user services and regulated search services. With duties related to legal but harmful content only applying to category 1 providers, we fear that legal but harmful content will free to propagate amongst all other providers and services. Taking the recent shooting in Buffalo as an example.

In the wake of the Buffalo shooting, which saw the tragic and fatal shooting of 10 people in Buffalo, New York streamed live on multiple platforms, this content has since been shared on other online platforms and presents the opportunity both to consider and test the duties and categorisation of providers drafted within the Online Safety Bill.

- The attack was initially live-streamed on Twitch which appears to have removed the stream within 2 minutes, with Meta’s platforms taking down copied videos/ posts within 10 hours only after it was shared 46,000 times. As category 1 services, is this what would have been expected?

- The content was subsequently widely shared on other large online services (e.g. Reddit, 4Chan, 8Chan) - would these platforms be categorised and registered as category 1 or 2 services, which would determine the extent to which their duties apply?

- However, the content remains on many other independent sites a week later, specifically so called ‘gore sites’ and has been viewed millions of times. Report Harmful Content has managed reports relating to the incident. As we understand, we anticipate that the majority these sites will fall outside the scope of the Online Safety Bill and as such fear that as drafted, despite this content being particularly harmful and universally available, this falls beyond the scope and jurisdiction of the Online Safety Bill? Indeed it may appear that beyond categorised services, there is little to prevent the availability and spread of harmful content

- Category 1 services have not yet been published which is leading to speculation about which providers and services would fall in scope to remove this type of content. For transparency and to avoid providers disaggregating their services, we would suggest that categorisation occurs by provider rather than service.

Report Harmful Content have responded to 1482 reports between January 2021 and May 2022. Of these reports 62% were regarding content not hosted on the 26 commonly used platforms detailed on the service’s website: https://reportharmfulcontent.com/report/. These range from less commonly used social networks, encrypted messaging apps and streaming sites, forum boards and 3rd party applications. 60% of the content falling into this category was hosted on independent sites which would, as the Online Safety Bill is drafted, not be considered in scope. Where is the mechanism for holding these sites to account? SWGfL’s helplines use a number of ways to contact these type of sites via their hosting providers where moderation/ reporting is not available and would contribute this experience in subsequent discussions about services in scope and definitions of legal but harmful content

Super Complaints

Part 8 — Appeals and super-complaints Chapter 2 — Super-complaints

SWGfL notes the details relating to ‘super-complaints’ and that “An eligible entity may make a complaint to OFCOM that any feature of one or more regulated services, or any conduct of one or more providers of such services” is “causing significant harm to users of the services or members of the public, or a particular group of such users or members of the public”

An entity is an “eligible entity” if the entity meets criteria specified in regulations made by the Secretary of State. There are no details as to the criteria and therefore no ‘eligible entity’.

Details have to be published regarding the criteria that an entity must meet in order to make a complaint to Ofcom and how this will provide redress for victims

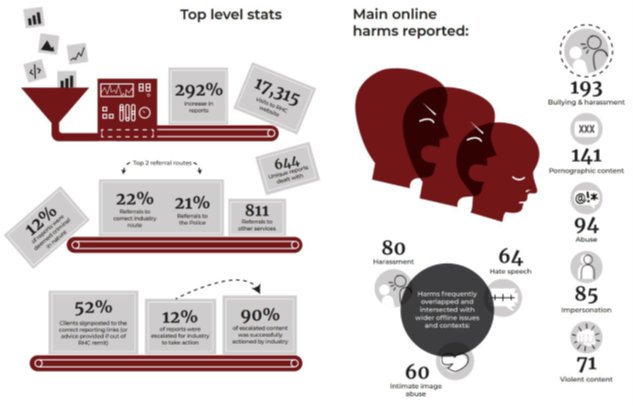

Annex A –ReportHarmfulContent Annual Report 2021 Headlines | SWGfL

Summarised breakdown of reports processed by category of defined legal but harmful content

The report also highlighted three common trends associated with legal but harmful content reports

- Cluster of domestic abuse, coercive control and harassment issues. This trend disproportionally affected women and in a quarter of cases involved intimate image abuse as an additional harm

- A 255% rise in reports with a wider issue of hate-speech. Most reports had a primary issue type of harassment or abuse

- Young males actively searching for harmful content and reporting it, for example harmful pornography was the only harm that was predominantly reported by males